I may have mentioned that the telcos and cablecos seem to like to game

legal and regulatory systems in their favor.

There’s another group of companies doing the same thing:

I may have mentioned that the telcos and cablecos seem to like to game

legal and regulatory systems in their favor.

There’s another group of companies doing the same thing:

If there was ever an example of why the DMCA needs to die, this is it. The idea that a sixteen-digit number is illegal to possess, to discuss in class, or to post on a news site is offensive to a country where free speech is the first order of the Constitution. The MPAA and RIAA are conspiring to unmake America, to turn this into a country where free expression, due process, and the rule of law take a back-seat to a perpetual set of governmental handouts intended to guarantee the long-term profitability of a small handful of corrupt companies.Why would the activities of the Motion Picture Association of America and the Recording Industry Association of America be worth such a polemic by Cory, who after all lives partly by copyright in his hat as a science fiction writer?—EFF explains the law on AACS keys, Cory Doctorow, boingboing, Wednesday, May 2, 2007

Cory’s rant was set off by EFF’s writeup on the attempts by Advanced Access Content System Licensing Administrator (AACS LA) to put the keycode horse back in the barn of AACS after somebody intercepted a keycode, posted it, and thousands of people have reposted it throughout the Internet, on t-shirts, fortune cookie paper slips, etc.:

Is the key copyrightable?Ed Felton explains why letting some company or organization claim ownership of a number (albeit by a legal dodge such as that describe above) is a bad idea. His first reason is that people don’t like censorship.

It doesn’t matter. The AACS-LA takedown letter is not claiming that the key is copyrightable, but rather that it is (or is a component of) a circumvention technology. The DMCA does not require that a circumvention technology be, itself, copyrightable to enjoy protection.&mdash 09 f9: A Legal Primer, Fred von Lohmann, EFF, 2 May 2007

The second part of the answer, and the one most often missed by non-techies, is the fact that the content in question is an integer — an ordinary number, in other words. The number is often written in geeky alphanumeric format, but it can be written equivalently in a more user-friendly form like 790,815,794,162,126,871,771,506,399,625. Giving a private party ownership of a number seems deeply wrong to people versed in mathematics and computer science. Letting a private group pick out many millions of numbers (like the AACS secret keys), and then simply declare ownership of them, seems even worse.While it’s obvious why the creator of a movie or a song might deserve some special claim over the use of their creation, it’s hard to see why anyone should be able to pick a number at random and unilaterally declare ownership of it. There is nothing creative about this number — indeed, it was chosen by a method designed to ensure that the resulting number was in no way special. It’s just a number they picked out of a hat. And now they own it?

As if that’s not weird enough, there are actually millions of other numbers (other keys used in AACS) that AACS LA claims to own, and we don’t know what they are. When I wrote the thirty-digit number that appears above, I carefully avoided writing the real 09F9 number, so as to avoid the possibility of mind-bending lawsuits over integer ownership. But there is still a nonzero probability that AACS LA thinks it owns the number I wrote.

— Why the 09ers Are So Upset, by Ed Felten, Freedom to Tinker, Thursday May 3, 2007

But it takes Bruce Sterling to spell out what’s really behind all this. Why would anyone think they could get away with owning random numbers? Or, more to the point, who?

(((Wait till Cory figures out that it isn’t even COMPANIES making all the handout money, but a tiny, conspiratorial, silk-hatted elite of hyperovercompensated CEO moguls…. Wow, that’ll make a great WALL STREET JOURNAL investigative report after Rupert Murdoch buys the paper.)))— Cory Doctorow Discovers Modern Russia, Bruce Sterling, Beyond the Beyond, 3 May 2007

I think maybe somebody already wrote the slant the WSJ would likely take after a Murdoch takeover:

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed — for lack of a better word — is good.The really ironic part is that what Michael Douglas’ character was complaining about in that movie speech was overpaid corporate executives. Only an even more overpaid corporate raider could get away with it….Greed is right.

Greed works.

Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.

Greed, in all of its forms — greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge — has marked the upward surge of mankind.

And greed — you mark my words — will not only save Teldar Paper, but that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA.

—Gordon Gekko, Wall Street, 1987

The attempts by RIAA, MPAA, and AACS-LA to lock up your computers, whether you use them to view Hollywood movies and listen to hit songs or not, don’t benefit the individual musicians all that much, except possibly for a very few of the biggest hitmakers. Any resulting profits won’t go to the average worker in the music or movie industries, either. Who they benefit most is a tiny number of greed-is-good executives, who end up getting paid even more when they retire and float down on their golden parachutes.

I’m not saying rich is bad. Take Lee Iacocca, for example, who famously persuaded the U.S. government to bail out Chrysler when he was its CEO. Nonetheless, he’s currently speaking out on issues that some of his CEO-club associates may wish he’d shut up about.

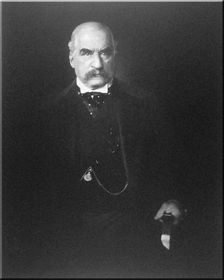

I am saying I see no reason why we should let a tiny group of individuals reap huge profits by gaming the legal and regulatory systems in ways that adversely affect 99.999 percent of the rest of us. What was good for J.P. Morgan in the Gilded Age ain’t necessarily good for us now. I think this is as true of the music and movie industries as it is of the telco and cableco Internet local access duopoly.

-jsq